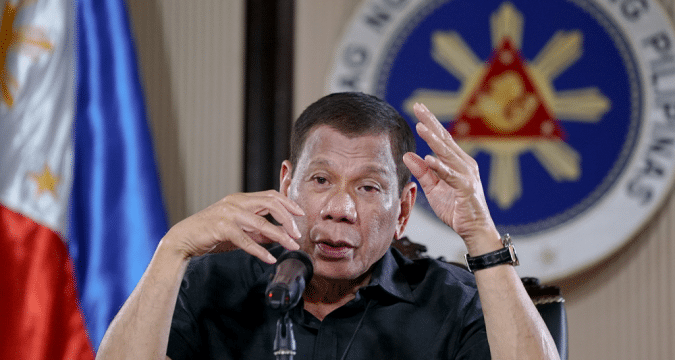

MANILA (UCAN): “The bill is a glaring attempt to silence critics and destroy any disagreement against the government, and consequently stifle people’s freedom of expression, academic freedom, right to organise for human and social development, and even freedom of the press,” Bishop Jose Bagaforo of Kidapawan, chairperson of Caritas Philippines, said after it emerged that Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte, had signed the controversial anti-terrorism bill into law on July 3.

The bishop called the newly enacted law “inhuman and unjust” as it threatened freedom, justice and compassion.

Executive secretary, Salvador Medialdea, confirmed to the media that Duterte signed the bill, now known as Republic Act No. 11479, despite calls from human rights and Church groups to veto the bill due to its constitutionally sweeping and ambiguous provisions.

Duterte certified the bill as “urgent” amid the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic (SARS-CoV-2), allowing lawmakers to fast-track its reading and approval within one day.

United Nations Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet, at the start of the 44th session of the United Nations Human Rights Council on June 30, in Geneva, Switzerland, had called on Duterte to refrain from signing the controversial bill due to the “blurring of important distinctions between criticism, criminality and terrorism.”

Bachelet said, “I urge President Duterte to refrain from signing the anti-terrorism bill as it blurs important distinctions between criticism, criminality and terrorism,” as she warned of its “chilling effects” on human rights in a report on the Philippines which also addressed Duterte’s alleged human rights violations in his war on drugs.

However, presidential communications chief, Martin Andanar, claimed the Duterte government had “simply responded” to a global call to fight terrorism.

“As the president is heavily afflicted by terrorism, as reflected in its ranking in the Global Terrorism Index of 2019, the Duterte administration stands firm in its position of undertaking stricter measures against terrorists,” Andanar said, adding, “Let us all work together to defeat terrorism and fulfill the president’s vision of a safe and secure, terrorism-free Philippines.”

Human rights and church groups, however, remain unconvinced by Andanar’s statement, saying the law would stifle the rights of Duterte’s critics.

As we celebrate the 500 years of Christianity in the Philippines. The Chaplaincy to Filipino Migrants organises an on-line talk every Tuesday at 9.00pm. You can join us at:

https://www.Facebook.com/CFM-Gifted-to-give-101039001847033

Rights group, Bayan Muna, said the definition of terrorism is vague under the new law noting in a statement, “Duterte could still pin down his critics and tag them as terrorists,” adding that it was particularly concerned over the provision in the law that punishes “incitement to commit terrorism.”

The group said, “The law creates a new crime, a very dangerous crime, as it empowers the president or the executive branch to file a case against anyone by mere inciting to terrorism. This creates a chilling effect among activists and dissenters of the government.”

In Geneva on June 30, Carmelite Father Christian Buenafe, speaking on behalf of the Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund, Franciscans International, Task Force Detainees of the Philippines and the Association of Major Religious Superiors of the Philippines, enumerated human rights violations such as arrests, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances and torture.

He mentioned Sister Mary John Mananzan and Ritz Lee as prominent defenders, who have been red-tagged (branded communist rebel supporters) by the government (Sunday Examiner, July 5).

Amnesty International said the Duterte administration had effectively crafted a new weapon to brand and hound any perceived enemies of the state.

“Under Duterte’s presidency, even the mildest government critics can be labelled as terrorists. This law is the latest example of the country’s ever-worsening human rights record,” the rights group said on social media.

Clergy of the Archdiocese of Manila released a statement saying the Philippine government could turn into the very terrorists the law claimed to protect the people from.

They referred to the Martial Law era when late strongman, Ferdinand Marcos, silenced critics either by killing or torturing government dissenters.