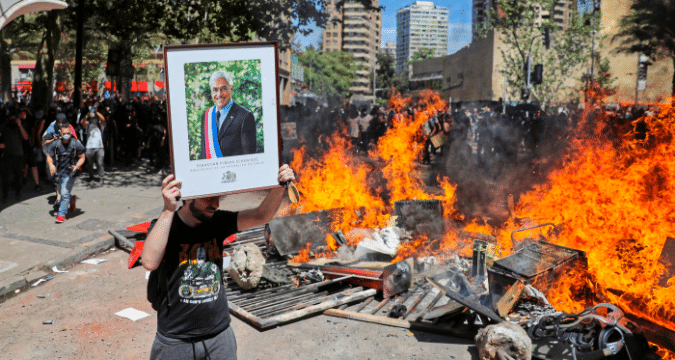

Students jumping the turnstiles in protest against a 3.7 per cent rise in metro fares on Santiago’s transport system in October last year, signalled the unleashing of a chain of events that would see the streets of the Chile’s capital city swamped with angry crowds demanding substantive changes in government policy.

More than the straw that broke the camel’s back, it came like a desert wind fanning long smouldering embers of discontent into a full-blown fire, leaving angry crowds rampaging through the city and battling the police and military forces called out by the president, Sebastián Piñera, to quell them.

Piñera is not new to mass demonstrations. He had been president when there were large student-led rallies in 2011, as those from new demographic areas who had signed up to a government study loan scheme some 10 years previously discovered that their expensive education was second-rate at best and only qualified them for low paid jobs that would leave them debt strapped for decades.

Praised at the time of its introduction as a forward-looking plan to address the country’s large income gap, the loan scheme saw over two-thirds of all students at universities across the country belonging to the first generation of their families or villages to achieve such status.

However, as the fallacies of promised social mobility became more apparent, anger overflowed into large-scale protests.

The failure of the programme had also unmasked other issues destined to become a major brunt of anger, especially the shortcomings of privatisation of not only education, but health care, water resources and public transport as well.

In addition, this has been aggravated by a growing mistrust in the efficacy of government and the demise of Chile’s economy from its former tiger status to pussycat.

Chile had made progress economically following the end of the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in 1988.

It had moved away from the extreme neo-liberal orthodoxy to a push towards growth with equity in a serious push to redistribute wealth (it has one of the highest Gini Coefficients in the world).

While it did succeed in cutting extreme poverty from some 30 per cent to around nine per cent, it failed to touch the resources of the top one percent that controls around one-third of the nation’s wealth.

Instead, the modest income of the middle class was redistributed among the lower economic echelons, where it made only slight improvements at the expense of the already not-so-well-off, creating a new tier of the financially struggling.

Writing in Dispatch in October last year, Jimmy Langman says that mounting debt in these two groups has been feeding public anger over the past decade, as only some 20 per cent of the population find themselves able to earn more than enough to pay for basic services.

Despite the economic growth of the past, this imbalance has seen tensions build to boiling point among the debt-strapped majority and the rise in metro fares proved the trigger to releasing the valve holding the steam at bay.

Government responded with offers of increased basic wages and pensions aimed at easing tensions, but these were dismissed as being too little, too late.

David Altman, a political scientist at the Pontifical University of Chile, describes the people of Chile as lacking an effective voice on the political stage.

With the real power of government contained within the presidential office, the people’s elected members of the congress have little ability to affect policies one way or the other and, in addition, are perceived by the general population as disinterested in the plight of the struggling 99 percent and often corrupt.

With little other opportunity to make their voices heard, Altman notes the people have opted for mass rallies in public places, the tossing of a few Molotov cocktails, blocking roads and vandalising both public and private property in an effort to make their voices heard.

Speaking from Santiago, Columban Father Dan Harding describes the events of the street as often being without rationale. Some three-quarters of the infrastructure of the city’s transit system that carries two million people a day has been damaged.

The situation was not helped by the heavy-handed response of the government when it called the troops into the streets to restore order.

The high casualty rate and numerous injuries among both police and people, including lost eyesight from rubber bullets fired by the authorities, has only added more fuel to the fire burning in the hearts of the people.

However, unlike the 2011 demonstrations that were student-led, the current unrest is spontaneous, spurred by the common conviction that something has to change in the country, and change profoundly and quickly.

Speaking from Santiago, Columban Father Dan Harding describes the events of the street as often being without rationale. Some three-quarters of the infrastructure of the city’s transit system that carries two million people a day has been damaged.

Serious damage has been wrought in universities, embassies, libraries and even records offices. Historic churches have been attacked, their pews set alight and valuables looted.

Small family businesses place handwritten signs outside their premises reading, “Please don’t destroy, we are a family business,” but mostly to no avail.

Father Harding says some 100,000 jobs have been lost and there is fear among the poorest people, especially migrants from Haiti and other disaster states, that they will be the next on the chopping block.

At the other end of the pile, big business is already taking its money out of the country.

He describes particularly violent groups that bully ordinary people, sometimes making motorists and passengers on busses get out on the streets and dance in front of them, just for the sake of humiliation.

He writes of widespread looting taking place, mostly by organised criminal elements and drug traffickers. In addition, he says that many of the poor believe that they have a right to loot properties.

“They have a sense of entitlement, as they believe a fair share of the economic pie has been unjustly withheld from them,” he says.

Nevertheless, he notes that the illogicality of the situation is that everything being done is in a profoundly righteous cause—the struggle for a more just and equitable society.

Consequently, even those, and probably a majority, who would rather rally peacefully, are prepared to tolerate the consequences of the violence because they adhere strongly with the agenda being expressed.

But with a referendum slated for April that could open the way for change to the dictatorship era constitution (1980), whose legitimacy has always been under a cloud, there is now a cautious optimism.

The 2011 demonstrations were led by Giorgio Jackson, now a 32-year-old member of congress. He believes this could open the way towards dismantling the mess of the privatised water, health care and education.

Nevertheless, Jackson fears a repeat of the past. “Political parties in this country always seem to reach agreements that don’t make much difference,” he said.

Father Harding describes the promise of a referendum as good news, even though conflict continues and the damaged infrastructure of the city and lost law and order will bequeath an onerous legacy to the building of a better and fairer society.

Jim Mulroney