Mary Aileen D. Bacalso

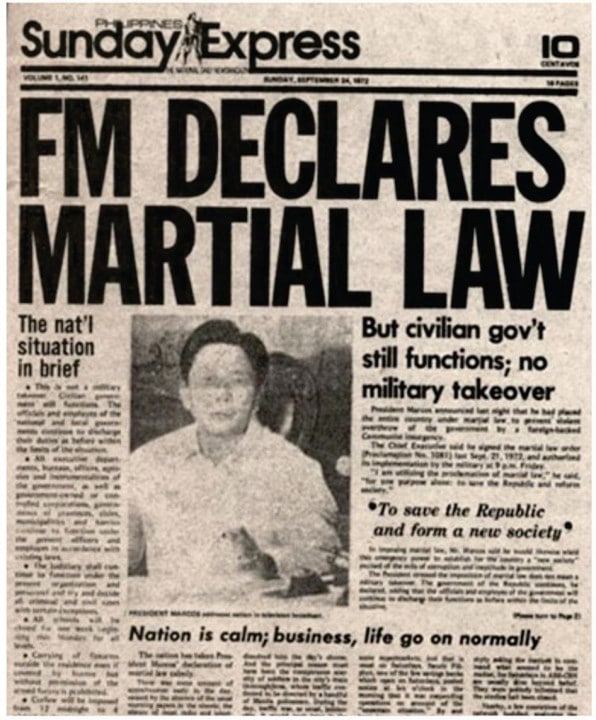

Almost five decades ago, on 21 September 1972, then-president, Ferdinand Marcos, declared martial law in the Philippines.

It was the day freedom and democracy died, when Marcos signed Proclamation Number 1081 that would impose military rule. Two days later, the imposition of repression was officially announced.

A nine-year-old girl when martial law was declared, I learned about its implications from my father. Press freedom was curtailed, media outlets were shut, while political opponents such as senators Benigno Aquino, Jose W. Diokno and Jovito Salonga were incarcerated.

Many others languished in jail and were tortured. Student demonstrations in Manila were dispersed and activists earned the ire of the powers-that-be. The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus was suspended and Congress was dissolved.

For almost my whole student life, I witnessed Martial Law and its horrors. It was during my college years, when St. Theresa’s College in Cebu incorporated social orientation in student activities, that I was exposed to the life of the urban poor and workers during demolitions and strikes.

In the hinterlands of Cebu, I immersed myself with farmers who were forced to sell their land at a very cheap price to give way to a golf course or sports complex. I witnessed demonstrators being tear-gassed, including the disappeared priest, Father Rudy Romano, who in his white cassock, was on the front lines.

The media, workers, rural and urban poor, students and all sectors of society who opposed the tyrannical regime suffered under the iron fist of repression in various forms—imprisonment, torture, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, massacres

The media, workers, rural and urban poor, students and all sectors of society who opposed the tyrannical regime suffered under the iron fist of repression in various forms—imprisonment, torture, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, massacres

At least 10,000 victims filed a class suit before the US Federal Court in Hawaii and years later won the case against the Marcoses.

In the course of their response to the signs of the times, and in solidifying Vatican II’s “preferential option for the poor,” members of the progressive segment of the Church were not spared the harsh repression.

In my years of social action work, I learned about the raids on social action centres and forged friendships with persecuted Church people.

As we celebrate the 500 years of Christianity in the Philippines. The Chaplaincy to Filipino Migrants organises an on-line talk every Tuesday at 9.00pm. You can join us at:

https://www.Facebook.com/CFM-Gifted-to-give-101039001847033

A North American priest, Father Edward Gerlock, was the first priest imprisoned during martial law. Five decades later, his recollection of what happened remains vivid.

“I was arrested the first day of martial law but it was house arrest. A few months later, I was brought to Camp Crame. The US embassy offered to help, but only if I agreed to leave voluntarily. The nuncio offered to help [but only toothpaste!],” he said.

“In the meantime, Nena Diokno, wife of the late senator, Jose Diokno, sent me a note [saying] that if I decided to stay, she would find me a lawyer. In the meantime, I was moved from [national headquarters of the Philippine National Police Camp] Crame to an immigration prison.

‘I was arrested the first day of martial law but it was house arrest. A few months later, I was brought to Camp Crame. The US embassy offered to help, but only if I agreed to leave voluntarily. The nuncio offered to help [but only toothpaste!]’

Father Edward Gerlock

“The best day of my whole life was the day we entered the immigration courtroom. I saw the face of Commissioner Edmundo Reyes when he saw our lawyers. Senator Lorenzo Tañada was next to me. Wow! What a look! Tañada told me that every country has very loose immigration laws so that they can get rid of ‘undesirables.’

“Colonel Rolando Abadilla and squad came to the Asian Social Institute and bodily carried me out of the building and out to the airport. I hid my passport under the mistaken notion that you cannot be deported without a passport. Abadilla looked at me and said: ‘If they allowed me, I would get that passport from you!’ I had no doubt he would. The trial dragged on for 13 months. Finally, I was allowed to stay and had to report to immigration monthly.”

Father Gerlock survived to tell his story. Many others did not. That we may remember, they include Father Nilo Valerio, beheaded but his remains are missing; Father Zacarias Agatep, shot dead; Father Edgar Kangleon, killed in Samar in a supposed car accident; Father Rudy Romano, disappeared and never found; and Father Tulio Favali, brutally shot dead in North Cotabato.

They are among those whose names are engraved on the Wall of Remembrance—a memorial to those who perished during the Marcos regime and whose martyrdom should constantly remind us of our part in this long struggle for social transformation.

In February 1981, during the visit of Pope John Paul ll to the Philippines, after the nominal lifting of martial law a month earlier, the Holy Father said in a televised message: “Even in exceptional situations that may at times arise, one can never justify any violation of the fundamental dignity of the human person or of the basic rights that safeguard this dignity.”

During those dark years, the courageous archbishop of Manila, Jaime Cardinal Sin, who made his presence felt by his flock until the very end of the anti-dictatorship struggle during the five-day EDSA People Power revolution in February 1986, constantly accompanied the progressive segment of the Church. His prophetic voice inspired many Church people to respond to the gospel imperative of following Christ’s footsteps and of becoming instruments to justice and peace.

Rights violations worse under Duterte

Martial Law resulted in untold violations of human rights of the rich and poor alike. While victims saw some reparation measures provided for them, sadly, the dream for a better Philippines that our heroes and martyrs lived and died for is far from being realised.

Having seen repression and resistance, I can honestly say that the human rights violations during the six years of the Duterte administration are worse than those during the 21 years of Marcos’ reign.

No less than the present head of state, in a speech made in December 2018, said: “These bishops that you guys have, kill them. They are useless fools. All they do is criticise.”

‘It is like living in the valley of death—the killing of drug users and opponents; helpless deaths in the pandemic, death by governance without vision, death by shameless corruption that seems to break all records’

Archbishop Peralta, Archbishop and Archbishop Bacay

Like the Marcos regime, the present administration has its record of killing Catholic clerics. The killings of Father Mark Anthony Ventura, Father Marcelino Paez and Father Richmond Nilo in the name of the war on drugs are examples of the persecution under the present administration.

When asked about the role of Church people in this equally dark or even darker period in our history, a nun from the Religious of the Good Shepherd, Sister Zenaida Pineda, who, with another nun, Sister Pilar Verzosa, was imprisoned by the Marcos regime, responded: “We have to always be at the side of the oppressed. We have to defend human rights.”

She shared my opinion that the present administration is even worse.

In a joint statement dated September 11, Archbishop Marlo Peralta of Nueva Segovia, Archbishop Socrates Villegas of Lingayen-Dagupan and Archbishop Ricardo Bacay of Tuguegarao said: “We have a moral duty to resist and correct a culture of murder and plunder as much as the prolonged pattern of hiding or destroying the truth” [Sunday Examiner, September 19].

The archbishops added: “It is like living in the valley of death—the killing of drug users and opponents; helpless deaths in the pandemic, death by governance without vision, death by shameless corruption that seems to break all records.” They ended their statement with a call for penitence and atonement.

Almost five decades since the declaration of martial law and 40 years after Marcos lifted it in 1981, authoritarian rule and all its devastating consequences to human rights and dignity remain deeply embedded in Philippine society.

Let a thousand prophetic voices chat. UCAN

Mary Aileen D. Bacalso is president of the

International Coalition Against Enforced Disappearances [ICAED].

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily

reflect the official editorial position of UCAN.