Jose Mario Bautista Maximiano, UCAN

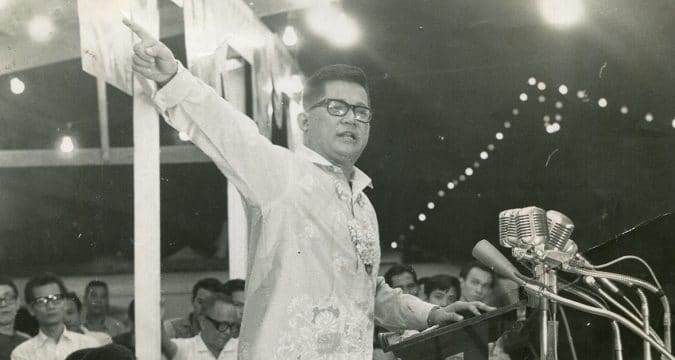

“I have asked myself many times: Is the Filipino worth suffering, or even dying, for? Is he not a coward who would readily yield to any coloniser, be he foreign or homegrown?” the late senator, Ninoy Aquino, said in his speech on 4 August 1980, at a convocation of the Asia Society in New York City.

He continued: “I have carefully weighed the virtues and the faults of the Filipino and I have come to the conclusion that he is worth dying for because he is the nation’s greatest untapped resource.” That was three years before he was assassinated.

Philippine dictator, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., didn’t know that Aquino, his political archnemesis, was a tougher nut to crack. The opposition senator was unstoppable in speaking up against the abuses of martial law [1972 to 1986] as he presented himself as the “peskiest thorn in Marcos’ side.”

Once he conveyed his willingness to die for his country with wit and humour: “‘I would rather die a glorious death than be killed by a Boston taxicab.”

You see, during martial law, death threats were whispered among Filipino political exiles, and Ninoy himself knew the real and present dangers to his life. On the day he died—21 August 1983—he said in an inflight interview on China Airlines that “if it’s [my] fate to die by an assassin’s bullet, then so be it.”

I return from exile and an uncertain future with only determination and faith to offer—faith in our people and faith in God

Earlier, he had drafted a speech he was to deliver on the day of his arrival and a copy of that speech, though undelivered, was kept by the New York Times and published the day following Ninoy’s martyrdom.

In that speech, the icon of democracy in the Philippines recalled that in one of the long corridors of Harvard University are carved in granite the words of Archibald Macleish: “How shall freedom be defended? By arms when it is attacked by arms; by truth when it is attacked by lies; by democratic faith when it is attacked by authoritarian dogma. Always and in the final act, by determination and faith.”

He concluded the speech with these words: “I return from exile and an uncertain future with only determination and faith to offer—faith in our people and faith in God.”

As we celebrate the 500 years of Christianity in the Philippines. The Chaplaincy to Filipino Migrants organises an on-line talk every Tuesday at 9.00pm. You can join us at:

https://www.Facebook.com/CFM-Gifted-to-give-101039001847033

And the world acknowledges that Ninoy Aquino, bearing great faith in the Filipino people, died a hero and a martyr.

Now, during a presidential campaign rally at the Tarlac City Plazuela on April 2, the Uniteam of presidential candidate, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the tyrant’s son, put up a tent that partially blocked the Ninoy Aquino monument from view from the rally stage.

Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines, reacted and said that such an act showed a complete lack of respect, calling it a “desecration” of the slain hero’s statue.

I have carefully weighed the virtues and the faults of the Filipino and I have come to the conclusion that he is worth dying for because he is the nation’s greatest untapped resource

Was Ninoy wrong in believing that “the Filipino is worth dying for?” Bishop David asked as if to challenge the Filipino citizenry, a few weeks before the presidential election.

“If this is how we treat the memory of a man whose death helped save our country from the long dark years of tyranny and dictatorship, and whose blood watered the seeds of aspiration for the restoration of our freedom and democracy,” the good bishop said, “then it must be said that he was wrong in believing that ‘the Filipino is worth dying for.’”

In mid-April, the official Rodrigo Duterte Youth party-list representative, Ducielle Marie Cardema, filed House Bill 10833 in the Philippine Congress seeking to rename Ninoy Aquino International Airport [NAIA] as Manila International Airport [MIA]. In 1987, through Republic Act [RA] No. 6639 it had been renamed in Aquino’s honour.

Little did Cardema know that in 2004, an act of Congress, by virtue of RA 2956, also declared August 21 of every year Ninoy Aquino Day. The lawmakers believed that this official declaration of a national non-working holiday was meant “to commemorate the death anniversary of former Senator Benigno ‘Ninoy’ S. Aquino Jr.”

In effect, RA 2956 and RA 6639 sealed the truth that indeed Ninoy Aquino is a Filipino hero and martyr.

Cardema claimed in her bill that when the airport was “named NAIA in 1987 during the time of then-President Corazon Aquino” it was a self-serving and highly politicsed act in connection with her late husband.”

If this is how we treat the memory of a man whose death helped save our country from the long dark years of tyranny and dictatorship, and whose blood watered the seeds of aspiration for the restoration of our freedom and democracy,” the good bishop said, “then it must be said that he was wrong in believing that ‘the Filipino is worth dying for

Bishop David

Again, little did Cardema know that the late Corazon Aquino, herself a former president and an icon of democracy, “rejected the renaming of the airport for her husband, or the replacing of a Mount Rushmore-style bust of Mr. Marcos with one of Ninoy.”

She was above all petty politics, according to American journalist, Seth Mydans, who wrote a special report for the New York Times in 1986 titled, “A Martyr Enshrined: The Legend of Ninoy Aquino.”

In his special report, Mydans made this emphasis: Cory Aquino did not allow manifestations of any kind of special treatment for Ninoy or any member of her clan “in line with the president’s strict policy of not favouring her family.”

Second, the present name of the airport was an act of Congress and therefore a legislative act, not an executive or presidential order.

Hence, “there has to be a Congressional action to repeal Republic Act No. 6639 which renamed MIA to NAIA,” Martin Andanar, the communications secretary, said in an online press briefing from Malacañang Palace.

Ninoy’s death started a chain of events that would eventually lead to the People Power Revolution of 1986. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Third, little did Cardema know that in 2020, the Supreme Court [SC] junked a petition filed by lawyer, Lorenzo Gadon, seeking to nullify RA 6639 that renamed MIA as NAIA.

Ninoy Aquino felt something bad would happen to him should he return to Manila from his US exile. Almost touching the future, in a kind of premonition, he decided to come home.

He had constantly prepared himself to offer his dear life on the altar of sacrifice, which is precisely what happened as he stepped off a plane at Manila International Airport. The tarmac itself was a mute witness to his heroism.

The funeral march that followed was the day Filipinos stopped being afraid of powerful tyrants. Ninoy’s death suddenly transformed the opposition from a minor and negligible action group to a more united and formidable movement of the masses. His martyrdom galvanised the popular resistance to militarisation and inspired the Filipino spirit to fight back.

Ninoy’s death started a chain of events that would eventually lead to the People Power Revolution of 1986. And the rest, as they say, is history.

In his 2011 State of the Nation Address, then president, Benigno Aquino III, son of Ninoy and Cory, made known his inner thoughts: “As long as your faith remains strong—as long as we continue serving as each other’s strength—we will continue proving that ‘the Filipino is worth definitely dying for,’ ‘the Filipino is worth living for,’ and if I might add: ‘The Filipino is worth fighting for.’”

Jose Mario Bautista Maximiano is the author of MCMLXXII: 500-Taong Kristiyano, Volume Two [Claretian, 2021], and 24 PLUS CONTEMPORARY PEOPLE: God Writing Straight with Twists and Turns’ [Claretian, 2019].

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of UCAN.