Father Myron J. Pereira, SJ

The American scholar, Daniel Boorstin, once wrote an essay entitled, Tomorrow in the Republic of Technology.

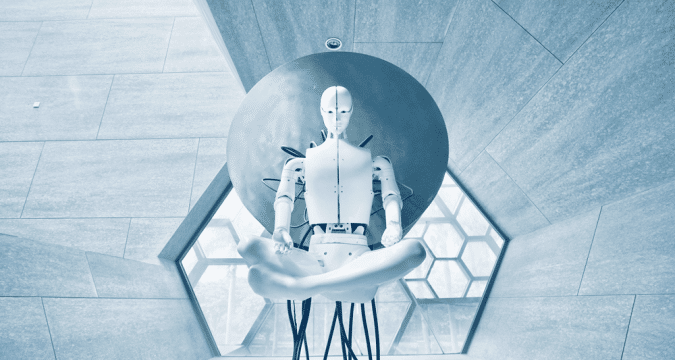

As the decades of the 21st century slip by, it is not hard to see technology as the driving force of all that is: faster, stronger, higher … faster! Imagine the future!

We live in the technosphere, most of us. Technology has become the faith of our contemporaries—the TV tower in place of the church belfry, the traffic signal instead of the wayside shrine, not forgetting that little gizmo in our hands connecting us to the rest of the world: the cell phone.

Satellite TV at home, AI in the office, smart cards everywhere … these are only the most obvious applications of a nervous system that already includes manufacturing, marketing, transport and medicine, and shows no sign of ever slowing down.

The film Star Wars predicted it all: the future will see a progressive interface between humans, machines and animals, where cyborgs, androids and robots will be as domesticated as cats and canaries, and as obedient as slaves and eunuchs once were. Imagine the future!

However, technology provides multiple options.

Technology has become the faith of our contemporaries—the TV tower in place of the church belfry, the traffic signal instead of the wayside shrine, not forgetting that little gizmo in our hands connecting us to the rest of the world: the cell phone

We aren’t speaking of the future, but of a future, one of many possible futures, or futurables. So, when we imagine the future, we’re also asking implicitly, what kind of future do I consider desirable?

Technology always promises two things: freedom and abundance. This means there’ll be more and more of the goodies of life, and no one will stop you from getting what you want.

For most of us in the Third World who have grown up in an economy of scarcity and constraint, that is “good news” indeed! Imagine the future!

But there are other ways of looking at the future, just as there is more than one way of reviewing the past.

Consider for a moment the greatest technological monuments of the ancient world, the pyramids. These funerary mausolea commemorate the grandeur of the divine pharaohs buried within. But who remembers the millions of slave labourers who built them with their toil and sweat?

The turn of the century began not just a new year, but a new millennium, and so gave us space to review history and re-imagine the future. Moreover, we could have done so not just as individuals, but as communities and nations

Who but the eponymous writer of the book of Exodus?

Indeed, what would the future look like when viewed from the underside of society?—through the eyes of the slave woman, the child worker, the migrant worker, the refugee?

This too is a dream for the future.

In 2000, almost 25 years ago, UNESCO launched a manifesto for a culture of peace. It pleaded for a “new beginning for us all to transform the culture of war and violence.” Imagine the future!

Not that this is a new idea. Three millennia ago, the Book of Leviticus in the Bible, described “the Lord’s Year of favour,” the Jubilee Year.

According to the writer, every 50 years [seven times seven years] should be a time of rejoicing, when those who had lost land, possessions, or freedom would be given all back gratuitously, when debts would be wiped out, and society would be renewed.

The turn of the century began not just a new year, but a new millennium, and so gave us space to review history and re-imagine the future. Moreover, we could have done so not just as individuals, but as communities and nations.

So, it is not so much technology that shapes our future—though it plays its part surely—as the right relationships between individuals and societies

But have we?

It doesn’t take much to see that were we courageous enough to accept the implications of reconciliation—as South Africa has been with its Truth and Reconciliation hearings—we would indeed have transformed society.

All of us indeed hunger for freedom and abundance, but often enough this abundance is hijacked by the greed of a few, and our freedom is curtailed by the fear of those in power, and we remain too timid even to protest.

So, it is not so much technology that shapes our future—though it plays its part surely—as the right relationships between individuals and societies.

Relationships of equity and justice, of peace and mutual acceptance, where none are excluded, and the poor, the weak, the displaced, the widowed, and the orphaned are specially cared for.

Can we imagine such a future? Can we will it into existence?

Someone once complimented the Nobel prize winner Alexander Solzhenitsyn on his writings and the tremendous imagination they revealed. “Imagination, ah yes!” replied the writer. “But I needed an even greater courage to bring imagination to fulfillment.” UCAN

*The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of UCAN.