Mary Aileen D. Bacalso, Manila

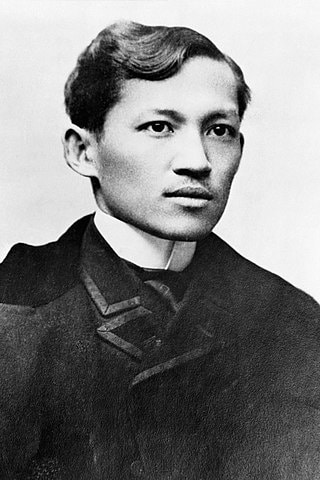

In the extraordinarily hard times of the coronavirus pandemic, the Philippines today commemorates the 124th anniversary of the tragic death of the country’s best and brightest, known as the greatest man the Malayan race has ever produced—national hero Dr. Jose P. Rizal.

An ophthalmologist by profession, Rizal resided and practiced in Hong Kong between 1891 and 1892.

By the might of his pen, he advocated reforms for a country that was under Spanish colonialisation. The author of two famous novels, Noli Me Tángere and El Filibusterismo, which are part of the curricula of all public and private schools in the Philippines, Rizal contributed in no small measure to the eventual birth of the Filipino nation. Both novels strongly criticised the political situation of the country under Spanish rule.

Voluminous chronicles of his life and works poignantly narrate that at 6.30am on 30 December 1896, Rizal left Fort Bonifacio, the place where he was detained, and sentenced to death. A bugler, a drummer and two Jesuit priests accompanied him. A squad of soldiers surrounded them and as they reached Bagumbayan (now called Luneta Park), he was positioned in the middle of 400 men. Eight native soldiers comprised the firing squad. Behind them were eight Spanish soldiers ready to shoot them if they would not shoot Rizal.

In a book titled, A Nation Aborted, by Floro Quibuyen, Rizal is considered as the Tagalog Cristo (the Tagalog Christ). He chose to bravely face his executioners at the very moment when the firing squad pulled the trigger. He died facing the sun.

The poem honestly expresses the author’s desire to die and to relish his eternal rest in his own enchanted land. Exclaiming that his soul will be departing from his body, Rizal reveals his firm belief in a world beyond the material.

In his literary masterpiece Mi Ultimo Adios (My Last Farewell), which I read in both Spanish and English, Rizal revealed the whole of himself—his sense of awe at the natural beauty of his beloved Philippines; his sense of gratitude to those who offered their lives to the altar of freedom; his heroism manifested in the ultimate sacrifice of his life so that one day we might witness the realisation of his youthful dream for his dear Philippines—the Jewel of the Sea.

The poem honestly expresses the author’s desire to die and to relish his eternal rest in his own enchanted land. Exclaiming that his soul will be departing from his body, Rizal reveals his firm belief in a world beyond the material.

Moreover, he summoned those who may one day visit his grave to kiss his soul. Humbly, he beseeched his country to pray for the eternal repose of his soul.

Mi Ultimo Adios reveals Rizal’s selflessness when he asked his motherland to pray for her suffering sons and daughters and for her own redemption—very obviously, her liberation from the bondage of colonialism.

As we celebrate the 500 years of Christianity in the Philippines. The Chaplaincy to Filipino Migrants organises an on-line talk every Tuesday at 9.00pm. You can join us at:

https://www.Facebook.com/CFM-Gifted-to-give-101039001847033

So deep was Rizal’s love for his country that he called on his beloved Philippines to listen to his singing even in death amidst the darkness and silence of the cemetery. Manifesting his altruism, he offered what would have been left of him—his ashes—to carpet the fields when he thought that perhaps, one day, he would have been totally forgotten, when his grave would have neither a tombstone nor cross.

Mi Ultimo Adios depicts the author’s self-sacrifice, his profound love for his country and his loved ones and, more importantly, his ardent faith in the afterlife—in Paradise—“where there are no slaves, no butchers, no oppressors” and where God reigns supreme.

He bade adieu to those who occupied the most special place in his heart—his parents, his sisters and brothers, his childhood friends, his sweet foreigner (his wife) whom he fondly regarded as his friend and his joy.

Lastly, he summoned his beloved country to be grateful for that very day when finally, he, the indefatigable man that he was, who needed his well-deserved rest, would have to die. As he said, “to die is to rest.”

Contribution to Philippine independence

“Rizal’s significance to our country’s history is best summed up in the title of Leon Ma. Guerrero’s book The First Filipino,” Francis Isaac, a researcher for Government Watch, said.

“It was Rizal who first saw the Philippines not only as a Spanish colony or a collection of islands in the Pacific, but as a distinct nation whose inhabitants are bound together by a common future. Though the country had more than 170 ethnic groups, Rizal argued that their shared experience of colonial oppression erased those differences and allowed them to forge a common consciousness.

“And because he saw the Philippines as a distinct nation, Rizal further asserted that it had the right to be independent. But independence, in Rizal’s mind, is not simply freedom from foreign domination but having a government that eschews tyranny and guarantees the rights and dignity of every citizen.

“This is clearly pointed out in his novel El Filibusterismo where we see Padre Florentino saying these words to the dying Simoun: ‘Why independence? If the slaves of today will be the tyrants of tomorrow?’ And though he reflected on the need for revolution, Rizal concluded that freedom cannot simply be secured through violence. Instead, his people should first have decent education and gain a sense of citizenship so that they can collectively shape the fate of the country once victory has been achieved.

“As he himself emphasised: ‘Our liberty will not be secured at sword’s point … We must secure it by making ourselves worthy of it. And when the people reach that height, God will provide a weapon, the idols will be shattered, tyranny will crumble like a house of cards, and liberty will shine out like the first dawn’.”

“As he himself emphasised: ‘Our liberty will not be secured at sword’s point … We must secure it by making ourselves worthy of it. And when the people reach that height, God will provide a weapon, the idols will be shattered, tyranny will crumble like a house of cards, and liberty will shine out like the first dawn’.”

Rizal had not taken up arms to join the armed struggle. However, his writings contributed, in no small measure, to whatever freedoms the present generation is enjoying. In the Pact of Biak na Bato (meaning, cleft rock), Rizal advised revolutionary leader, Andres Bonifacio, that an armed revolution could be an inevitable option if the situation demanded the shedding of blood as a necessary sacrifice rather than prolonging the agony of the Filipino people.

His Mi Ultimo Adios, which was handed by his brother, Paciano, and his wife, Josephine, to Bonifacio, had fanned the flames of the revolution. To a large measure, the poem contributed to the eventual dawning of freedom from colonial domination.

The rest is history.

If Rizal were alive during the pandemic

During the colonial period, the might of Rizal’s pen earned him the ire of his enemies. I share Isaac’s view that if he were with us during this pandemic, he would definitely criticise the (Philippine) government’s response to this malady.

Not known to many, Rizal survived a pandemic that swept some European cities from 1889 to 1890.

A survivor and a medical practitioner, he would surely offer his expert opinion on the measures that public authorities must take to contain the spread of the dreaded disease.

A survivor and a medical practitioner, he would surely offer his expert opinion on the measures that public authorities must take to contain the spread of the dreaded disease.

Like any genuine critic of the present administration, he would certainly be one of the key targets of the Anti-Terror Law and be tagged as either “yellow” or “red.” And like our contemporary human rights defenders, he would most likely be a key target of extrajudicial execution or enforced disappearance.

Rizal is widely recognised in the Philippines and the rest of the world. While all cities and municipalities in the country have his monuments erected, memorials of the Philippine national hero can also be found in 10 countries. I lived for many years in Rizal Street in my hometown in Sogod, Southern Leyte. I also had the opportunity to walk along Rizal Street (Jose Rizal Strasse) in Wilhelmsfeld, near Heidelberg, Germany.

Rizal did not die in vain. His patriotism and martyrdom will forever leave an indelible imprint that will always serve as a beacon of hope for his compatriots and for all the peoples of the world. Immortalised in the annals of history, Rizal’s words and deeds shall forever pave the way to the realisation of the Jewel of the Sea.

Sadly, present-day realities make such a dream seem very distant in the Philippines.

Mary Aileen D. Bacalso is president of the International Coalition Against Enforced Disappearances (ICAED). The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of UCA News.