This is the final part of the essay by Father Gianni Criveller of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions (PIME) on the missionary endeavours undertaken by the missionaries of Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions during their 150 years of history in China and Hong Kong. The first part was published in the previous issue of the Sunday Examiner on November 8

The PIME mission in China also had its share of limits and defects in a missionary era of lights and shadows. The most serious shortcoming was the delay in entrusting the leadership of the churches to the local clergy.

Inculturation of Christian faith in the Chinese context was also implemented with grave delay. This was due to opposition coming from within the missionary world, the interference of colonial politics and even due to the incoherent policy from the Holy See.

Occasionally some missionaries harboured nationalist sentiments which gave rise to a certain mixture of mission and imperialism.

In 1919, Benedict XV sought to correct the problem with the encyclical Maximun Illud. Immediately afterwards, Pope Pius XI sent Father Celso Costantini as apostolic delegate to China and he began his mission in Hong Kong.

The pope had instructed him to seek advice for his mission from Bishop Domenico Pozzoni PIME, the bishop of Hong Kong, who was a trusted friend of the pope.

Hence, as early as 1881, Bishop Volonteri reported to Rome about the need for an official delegate of the Holy See in Beijing. He was the first one to put forward this idea

Most PIME missionaries, and certainly its most significant leaders, were spared the anti-evangelical virus of nationalism.

Bishop Simeone Volonteri, founder of the PIME mission in Henan, opposed a French protectorate in the region and thought imperialist protection of missions was more harmful than useful.

He denounced the negligence of the so-called ‘protectors’ in fulfilling their task.

Hence, as early as 1881, Bishop Volonteri reported to Rome about the need for an official delegate of the Holy See in Beijing. He was the first one to put forward this idea.

Father Stefano Scarella, apostolic vicar in northern Henan, also refused an Italian protectorate over Italian missionaries in China. He opposed the anti-clerical Italian government, which suppressed the College of Chinese in Naples, the first institution that welcomed Chinese in Europe.

Martyr and saint, Alberico Crescitelli, wrote about it with bitter sarcasm: “I cannot understand how the Italian government, after suppressing the Chinese College, has the nerve to pretend to protect the Italian missions in China. A protection that is rather harmful for the purpose we came here for.”

Timoleone Raimondi, bishop of Hong Kong and Holy See’s procurator for the whole of China (he visited China missions on behalf of Pius IX in 1869), was also against the French protectorate and any other foreign protection.

Nationalism was, according to Raimondi, the cancer of the missions and French military protection was causing immense harm. “Without it,” Raimondi wrote to Rome, “we would be better and more respected Christians and missionaries.”

In 1885, Pope Leo XIII sent a delegation to China, led by Francesco Giulianelli, a missionary of the Roman Seminary of St. Peter and Paul.

Giulianelli had the task of establishing direct contact between the Holy See and the Chinese empire. The following year the pope decided to establish diplomatic relations with China. On 5 August 1886, the decision was published on the first page of L’Osservatore Romano.

France’s indefagitable opposition, however, sabotaged the plan. Pope Leo XIII “with tears in his eyes” had to yield to the pressure from France. It was, in the words of the pope, the greatest pain of his pontificate.

Even Costantini, the first apostolic delegate, who was in China from 1922 to 1933, had to overcome the opposition of the protecting power.

Diplomatic relations were established in 1946, with Archbishop Antonio Riberi as first nuncio and John Wu Qingxiong, friend and collaborator of Father Nicola Maestrini of PIME in Hong Kong, as first ambassador.

Giulianelli had the task of establishing direct contact between the Holy See and the Chinese empire. The following year the pope decided to establish diplomatic relations with China. On 5 August 1886, the decision was published on the first page of L’Osservatore Romano

Their experience in Hankou, China, was no different either. The bishop who had insisted on having them was out of residence and on their arrival, no one had prepared a home for the sisters. Yet these women have done nothing short of amazing things for the emancipation of girls, education and the promotion of women in the city of Hong Kong, in China and throughout Asia.

John Wu wrote The Science of Love, a short and beautiful book dedicated to St. Therese of Lisieux, patroness of the missions. His work deliberated on the perfect union of best of virtues of Confucianism and Taoism.

The advent of communism and the expulsion of missionaries seemed, for many years, the last word on Christianity in China and missions founded by our missionaries. The last PIME missionary in China, Brother Raffaele Comotti, left the Nanyang mission on 31 May 1954.

The cristianità founded by PIME continued their existence through the travails of persecution: arrests, imprisonments and trials. The fate of Chinese priests and faithful was even more painful than that of the missionaries. Their detention was longer and humiliation more devastating.

Many were called to confess their faith before the people’s courts, in prisons and in labour camps; some heroically offered their lives in martyrdom. The Catholic communities of Henan resisted the imposition of separation from the pope.

In the early 1980s, after the dark years of political campaigns, Deng Xiaoping inaugurated a new season, called “policy of freedom of religious belief.” The news from China had already begun to arrive since late 1970s. Particularly moving were the letters received from Father Domenico Maringelli from his “Christians of Anyang.” They were collected in a precious book by Piero Gheddo.

The PIME missionaries, Mario Marazzi and Giancarlo Politi among others, published over 20 books detailing the witness and sufferings by Chinese Christians to public knowledge.

In those years, PIME missionaries, within the free space granted by the authorities, resumed contact with their former communities and visited them, 40 years after their expulsion. The contacts with our ‘former missions’ were not for resuming a past gone forever, but to support brothers and sisters in their efforts in resuming Christian life.

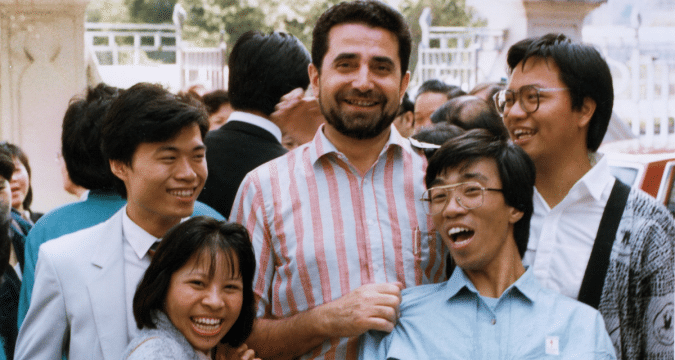

Their short visits to China were made in the spirit of friendship, concern and charity. They found, among difficult situations of division and suffering, encouraging signs of hope. Catholic communities resumed their religious life; seminaries and convents were reopened; adults asked for baptism. I remember Father Amelio Crotti narrating his emotional visit to Kaifeng in 1991, where he encountered his ‘Christians’ after four decades of separation.

I want to mention at least two PIME missionaries who have generously dedicated themselves to the cause of China in re-establishing contacts with the communities of Henan and Shaanxi. They are the indefatigable Father Angelo Lazzarotto, a man of dialogue and a thousand contacts. Today he is 95-years-old and spends his last years in the home for retired missionaries in Lecco (northern Italy).

Many were called to confess their faith before the people’s courts, in prisons and in labour camps; some heroically offered their lives in martyrdom. The Catholic communities of Henan resisted the imposition of separation from the pope

The other missionary is the late Father Giancarlo Politi, a missionary in Hong Kong, former director of Milan Missionary Centre and spiritual director of Monza Seminary. Politi, who passed away on 23 December, 2019, was a formidable collector of news about the situation of bishops and communities in China. I believe it was because of his remarkable competence that he was asked to work at the Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples.

In these first two decades of this century, PIME members visiting China dedicated themselves to supporting persons in need and serving people with disabilities, supporting non-governmental organisations and collaborating with faithful in Hong Kong and other local Churches. Among them, Father Mario Marazzi is still generously active in Hong Kong at the respectable age of 92.

The historical excursus, certainly incomplete, is aimed at showing that PIME’s attention to China is alive and is expressed in the ways that circumstances allow. And the discourse has to go back to Hong Kong, the city in which our Chinese mission was born and the only one that still continues.

Hong Kong is a wonderful and beloved city with beautiful natural landscapes, postmodern architecture and the most elegant skyline in the world. Even more beautiful are the people of Hong Kong, their resilience and their dignity.

Hong Kong has been, for a long time, a crossroads that harboured many meanings: a Chinese city under the authority of Beijing, which lived in freedom and tended to increase the space for citizens to participate in public affairs.

Times and circumstances are changing fast. The changing political spectrum and social polarization, coupled with the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic, a sense of distrust, demoralisation and helplessness is creeping into the lives of the faithful. Yet, we will not forget Hong Kong, its people, its Church and its missionaries.