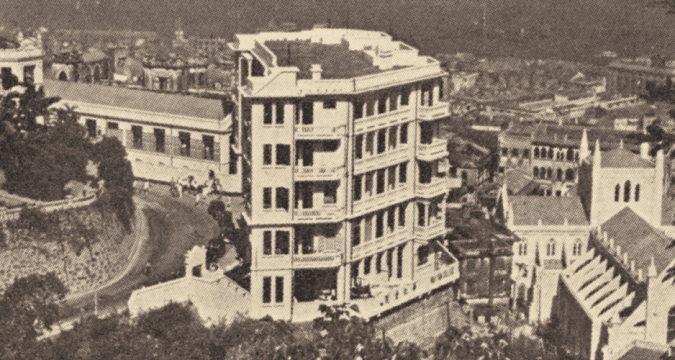

Wah Yan College, Hong Kong, the oldest Jesuit school in the Chinese Jesuit Province, is celebrating its centenary in 2019-2020. It was founded by Peter Tsui Yan-sau on 16 December 1919 to provide an English education to Chinese boys.

Starting with only four students, the school expanded steadily and by 1928, the student population already reached 800, the largest in the then-British Colony.

From planting to gathering

In December 1932, Tsui transferred the school to the care of the Jesuits who gave it the name, College of Christ the King. Interestingly, the name was never officially adopted, and Wah Yan College, Hong Kong continues to be used to this day. It shows respect for the founder as well as the Chinese culture.

The word Wah is generally taken to mean Chinese in our culture. The word Yan means benevolence, the highest virtue in Confucianism. Although the word Wah was said to come from the name of the founder’s hometown: Ng Wah, and the word Yan from his Chinese name: Tsui Yan-sau.

In the years since its founding, during which the world and the region have undergone tremendous changes, the school remained a place in which students learn, grow and develop in relative calm while striking lifelong bonds with schoolmates.

To date, over 10,000 Wahyanites have benefitted from the nurturing care of Jesuits and lay teachers. Many of them have gone on to make important contributions to Hong Kong and the world.

While the public more often recognises those who became prominent leaders or even pioneers in the academe, medicine, law, government, politics, commerce, entertainment and other fields, we are no less proud of those who are not so famous but who nonetheless contribute in small yet vital ways by faithfully performing their roles in society and family.

I will never forget a senior alumnus who came over to me during the 50th anniversary reunion of the Class of 1963 and said: “I was not a brilliant student back then, but Father Barrett (the principal then) told me that it’s okay. Just be a good man. I am glad to tell you that I have done it! I have been a good man throughout my life!”

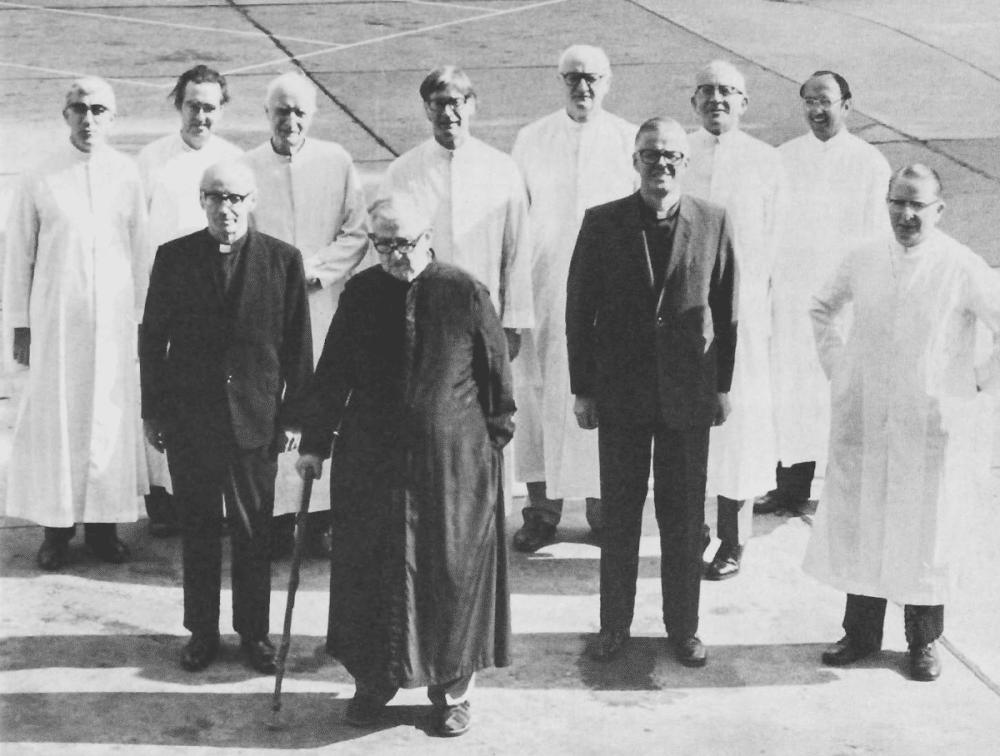

Since the Jesuit takeover, the faculty comprises both Jesuits and lay teachers. For example, in the 1980s, there were around 10 Jesuits and 30 teachers. However, since then, the number of Jesuits gradually fell.

In response, the school stepped up its formation of lay teachers on Ignatian pedagogy, including participation in Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific workshops and formation program for new staff members of the school.

The characteristics and values of Jesuit education were also made more explicit to teachers, students and parents through official documents and the curriculum. Networking with Jesuit schools in other parts of the world also increased.

Moving forward, we see it as vital to continue sustaining and developing our Jesuit characteristics by enhancing the system and method of forming lay teachers. The newly established Centre for Jesuit Education of the Chinese Jesuit Province would be helpful in this respect.

Photo: Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific

Freedom

Alumni have shown their deep gratitude towards the school through their strong support. What do they usually say about their alma mater? One word they utter, regardless of generation, is “freedom.” By this, they may each be referring to some aspect(s) of the Wah Yan education they experienced:

For example, they may be referring to the undogmatic approach, especially of the Jesuits, so that what is taught is not simply imposed from an authority above. Students learn not just the what but also the why.

Coupled with a discovery method in which students actually experience the process of knowledge construction, they will also find the learning more meaningful, authentic. There is more likelihood that this learning will be assimilated as their own and applied years after graduation.

Or they may be referring to the autonomy given to the Student Association, clubs and other student bodies as to how they organise their activities and manage their affairs. We encourage them to be engaged in a wide range of extra-curricular activities. The rich multifarious experience will contribute to the development of the whole person—attitudes, generic skills, hidden talents—that mere classroom learning will miss.

Or they may be referring to the open-mindedness of the school administration, such as in welcoming students’ ideas and dialogues on school rules. We want students to learn to think independently, to be both critical and constructive, and not to take things for granted, even if they are from the authorities.

Or they may be referring to the fact that the school does not shy away from controversial social and political issues and often organises talks, debates or discussion forums. We see controversies that touch students’ hearts as learning opportunities. Learning is to be understood in its widest sense, not confined to the formal curriculum.

We also want to inculcate in students one of our core values: unity in diversity. As societies and nations are increasingly being torn apart by extremism, what this core value can engender: respect, inclusiveness, humility, dialogue, sense of community has become ever more important.

While this is hardly a complete picture of Jesuit education at Wah Yan, it may provide a glimpse of some salient features of students’ learning experience here.

Moving forward in good

times and bad

Just as we are preparing to celebrate our centenary, Hong Kong is embroiled in deep political controversy and social unrest. Young people, including many university and senior secondary students, are among the most active in the movement as they feel, perhaps for the first time in their young lives, that they are participating in something they find deeply meaningful.

To respond to the situation, the school reflected on our vision, tradition and core values, and formulated a stance. On the one the hand, we acknowledge that our school is a place of learning, not a political organisation, and we should do our utmost to protect this mission. Thus, political activities, including propaganda from all sides, are inappropriate.

On the other hand, we should be open to, even welcome, explorations and discussions of opposing views. The school is not an ivory tower; we are preparing our students for the real world. Despite huge challenges, the school managed, on the whole, to hold on to its mission.

On reflection, the incident actually confirms the relevance of the Jesuit vision and approach to education at Wah Yan as shared in this article.

At the same time, it accentuates the challenges of this approach. For example, how can we walk with our youth without necessarily siding with them? How can we tread the fine line between objectively discussing emotionally and politically charged issues and inadvertently exerting undue influence? And how can we help our students find genuine hope in the midst of really tough circumstances?

These are not easy questions, but as Ignatian educators, we are called to do that which is meaningful, not that which is easy. With renewed vigour, the school is ready to take on the next 100 years, confident that we have something unique and valuable to offer to generations of young people to come, even in the most difficult of times.

Dr So Ying-lun

Wah Yan College, Hong Kong alumnus, former principal, director of the Centre for Jesuit Education of the Chinese Jesuit Province.